I’m happy to announce that the pre-launch for my upcoming novel, The Fugue, is underway. You can find pre-order information here at the CCLaP website. I also encourage people to check out what kind words Jason Pettus, CCLaP’s owner, left on the novel’s Goodreads page. “This is the literary novel for those who love literary novels…”

The Fugue started out back in 2000 when I was a student in New York. One night I wrote a vignette titled “Juri’s Window”. Juri was a painter and sculptor living in Amsterdam, perhaps in the mid 90’s, where he collected unemployment benefits and sculpted from trash. The vignette was simple: a description of a window Juri put together out of glass bottles and the remains of a discarded fence. I looked at it as a writing exercise.

But this character pestered me, kept appearing in my work. Soon the name had changed to Yuri, and he had a family, a girlfriend. Later, I moved him from Amsterdam to my hometown of Cicero, and his family gained a complex history of flight and displacement. Eventually he’d been accused of arson and murder. I realized I had a novel.

I messed around with various drafts for years. But in the summer of 2006, at that time working in Bloomington, Indiana, I felt the book, clocking in at about 135,000 words, was finished, and I started trying to sell it, going about it in the traditional way, sending cold queries to strangers.

Mind you, obsessed with The Fugue, I had not published a single piece of short fiction at that point. I don’t know how many rejection letters I collected—for a while I had been assembling them in a scrapbook, but in time I had no place to put them, and far from motivating me, they were just trash mail, most of them the usual form rejections. What kept me writing queries were the nibbles. This Midtown agent asked for the first 50 pages; that Chelsea editor asked for the manuscript. Now another agent wanted the whole thing. After reading, she told me her colleague might be a better fit and forwarded the text along.

The people who read it in whole or part all said about the same thing: “You don’t have a platform, and this book’s too difficult to market.” I took to heart that they didn’t say, “Your writing is shit.” It left me enough to maintain the feeling that I could be a writer. But I hung up The Fugue as a failure and set it under the bed, so to speak.

In the summer of 2007, I started writing Finding the Moon in Sugar, a project that occupied the years leading up to my first child’s birth in 2009. And then I took on smaller writing assignments, including a stint with The Good Men Project.

Part of the reason I self-published Finding the Moon in Sugar was to get my name out there. I wanted to have something gripping but fun to read from during events, and I thought the best way to learn how to market a book—a work of literary fiction, to the point—was to get out there and try to do it.

Last autumn, 2014, I was reading from Finding the Moon at RUI, a reading series here in Chicago. I hoped, at best, to sell a couple of copies, maybe learn about some new writers. At the bar, Sheffield’s, I ended up sitting next to a man, Jason, who had a lot to say about selling books. Turned out he had a publishing house. After my reading—I read the scene when Andy hears opera music for the first time—Jason asked me if I had any short stories. Sure, I said. I have plenty. But when I checked out his website, I figured, what the hell. Maybe I’ll tell him about The Fugue.

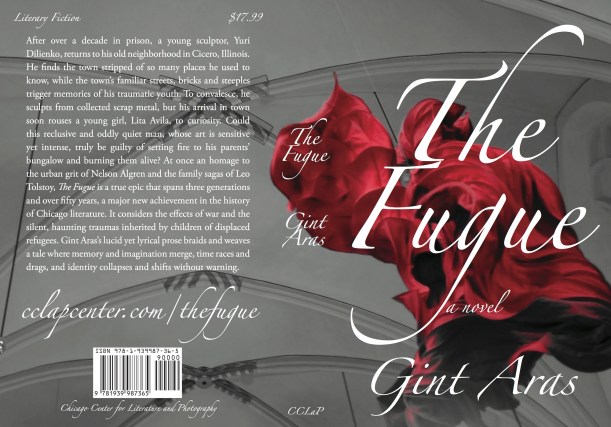

This holiday season, the book that started out as a vignette will hit the shelves and e-readers. In anticipation, have a look at the cover. It’s gorgeous:

You must be logged in to post a comment.